Good Migrations

All around us, birds are setting off on epic southward journeys. It’s fall migration season.

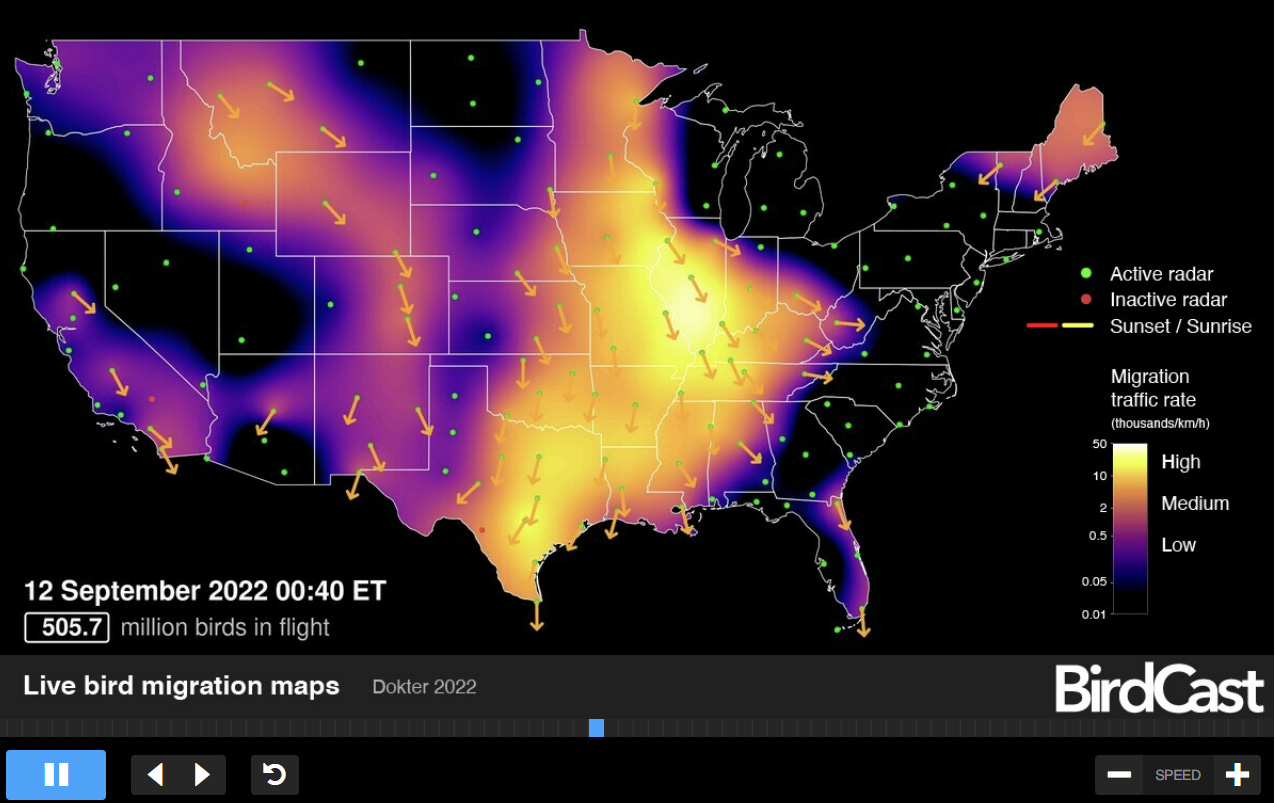

This awe-inspiring global phenomenon is somewhat hidden from us, sadly, since it happens mostly at night. The good folks at Cornell, Colorado State and UMass have come up with a workaround, though, in Birdcast, where you can get real time data on the who/what/when/where/how of these flight patterns.

I mean, just look at this image of the goings-on over the US just last night:

Also, you can plug in your county and get a geographically-specific readout like this:

Imagine: while I slumbered on September 8, more than 2 million birds flew over Montgomery County, MD, in search of better food and habitat than our northern-hemisphere winter would provide them.

Who’s crossing over your county these days? Click here to find out!

Some species, such as the cedar waxwing, may travel only a few hundred miles. (I say “only,” but you won’t see me volunteering to fly a few hundred miles under my own power!) The gray cheeked thrush, weighing in at just over one ounce (about the heft of a slice of bread), travels from northern Alaska and the Canadian subarctic to South American and back each year. Some of them will cross 600 or so miles of the Gulf of Mexico in one swoop. Nonstop! Over the course of a month and a half, arctic terns may cover 55,000 or more miles. That’s more than double the earth’s circumference.

How, you ask, do they perform these jaw-dropping feats of physical strength and endurance?

“Migratory birds can grow and jettison their internal organs on an as-needed basis, bolster their flight performance by juicing on naturally occurring performance enhancing drugs, and enjoy perfect health despite seasonally exhibiting all the signs of morbid obesity, diabetes and looming heart disease. A migrating bird can put alternating halves of its brain to sleep while flying for days, weeks or even months on end, and when forced to remain fully awake has evolved defenses against the effects of sleep deprivation; in fact, birds actually seem to get mentally sharper under such conditions….” – Scott Weidensaul

Not to mention how they use “quantum entanglement” to navigate. (Don't ask. I have no idea what that means.)

All of these superpowers notwithstanding, migration voyages are inherently perilous for birds. And true to form, we humans are compounding the dangers by chopping down forests, fragmenting woodlands, filling in wetlands, plowing under prairies, and generally destroying every natural habitat we can find. We’re paving over the stopover sites that make those spectacular commutes possible. Some studies suggest that as many as half of all migrating birds don’t make it back to their spring and summer grounds, due in large measure to man-made disruptions and threats along the journey.

So, what can we do to protect and support our feathered friends on their flights? Turns out there are plenty of ways we can step in as wingmen.

1. Provide Food from Native Plants

Sure, bird-feeders are fine, but they’re nowhere near sufficient. If we plant native species, we can provide a variety of food throughout the year for nesting, migrating and wintering birds. The four main food groups for birds are:

Bugs: native trees such as oaks, willows, birches and maples and native herbaceous plants such as goldenrod, milkweed and sunflowers host lots of caterpillars.

Fruit: many shrubs and small trees – such as serviceberries, cherries, dogwoods, spicebush, hollies and cedars – provide berries that ripen in successive seasons.

Nuts and seeds: Nuts from oaks, hickories and walnuts can be cached to provide fat and protein over the winter, while seeds of sunflowers, asters and coneflowers are go-to favorites of many small birds.

Nectar: Hummingbirds hanker for the nectar in red tubular flowers such as native columbine, penstemon, and honeysuckle.

2. Create Habitat Layers

Large canopy trees offer nest cavities and roosting spots, as well as nuts and insects to eat.

Shrubs and small trees serve up nesting sites, protection from the elements and berries.

Herbaceous plants, including perennials, annuals, and groundcovers, provide cover, nesting materials, nectar and seeds.

Decaying leaves, stems, detritus, and soil are home to many of the bugs that birds like to eat, including caterpillar pupae. You have The Bees’ Knees' blessings to lay off the deadheading and raking. Feel free to leave some brush piles lying around while you’re at it.

Dead trees and branches are gold. Standing tree trunks are valuable real estate for cavity-nesting species. And dead wood ultimately decays into rich soil that supports the entire food web. Those of us who have the space and landscape flexibility can leave stumps and snags in place and stash fallen logs and branches in out-of-the-way spots.

3. Add Water

Birds need water for drinking and bathing year-round. A bird bath can be as simple as a shallow dish. But if you’re looking to upgrade, bear in mind that a) birds find the sound of running water irresistible and b) mosquitoes won’t breed in moving water, so you might want to consider a drip bath or fountain feature. Also, maybe a water heater to prevent freezing in the coldest months?

4. Just Say No to Pesticides

Even pesticides that are not directly toxic to birds can pollute waterways and decimate the insects birds rely upon for food. Remember: a garden full of bugs is a magnet for birds. Also, a yard with a diversity of native plants will attract frogs, toads, bats, dragonflies, praying mantises and ladybugs, which will in turn prey on those plant-eating bugs, keeping everything in balance.

5. Keep Mittens Inside

I love me some kitties. But they’re efficient predators, downing one to four million birds in the continental U.S. each year. Even well-fed cats with bells on their collars can do lots of harm, so it's best to keep them indoors.

6. Eat Organic and Drink Shade-Grown

Every time we buy organic produce, we’re helping to decrease the demand for pesticides and thus the exposure to harmful chemicals birds are facing. When we insist on shade-grown beans for our pour-overs, we’re accomplishing more than impressing our friends: the large trees on shade plantations provide essential habitat for wintering songbirds.

7. Turn Out the Lights

Birds rely on light from the moon and stars to navigate. Artificial lights attract and disorient them, potentially throwing them off course and making them vulnerable to collisions with buildings. Switching off unnecessary lights – especially during peak migration season -- can greatly reduce these risks.

Migrating birds deserve all the help we can give them. Here’s to their safe journeys, and to our roles as caring wingmen. Here's to good (good, good, good) migrations!

Resources

Braelei Hardt, “How Do We Know Anything about Migrating Birds?” NWF Blog, August 31, 2022.

Scott Weidensaul, A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds, W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 2021.

“10 Ways to Help Migratory Birds,” National Wildlife Federation, April 14, 2010.

“How to Make Your Yard Bird-Friendly,” National Audubon Society, April 8, 2016.

“The Basics of Bird Migration: How, Why, and Where,” All About Birds, The Cornell Lab, August 1, 2021.

You’re supposed to be able to see and count migrating birds against the moon. With binos and scope. Haven’t succeeded yet but will continue to try.

Great post! Motus is another wildlife tracking system that monitors the migration patterns of not only birds, but bats and some insects. See https://motus.org